- Places

Still the most influential restaurant in London?

Thirty years on, St John remains the restaurant that redefined British dining — minimalist, mischievous, and endlessly imitated. From bone marrow to Bourdain, its legacy still shapes how London eats.

- Words By Ed Cumming

In late August last year, a large part of Britain — and indeed much of the world — was focused on securing tickets to the long-awaited Oasis reunion tour. The Britpop icons were coming back together, thirty years after their breakthrough album. Tickets sold out in minutes, so quickly that Prime Minister Keir Starmer felt obliged to comment on the scourge of resellers and the nation’s collective panic to secure a seat.

A few weeks later, however, there was an event even more in demand: the St John 30th anniversary celebration week. To mark three decades in business, Fergus Henderson and Trevor Gulliver invited diners to enjoy their trailblazing menu at 1994 prices. A roast bone marrow and parsley salad was £4.20 (compared to £16 in 2024); tripe and onions £7.80; a Welsh rarebit £3.50. Their signature pudding — an Eccles cake served with a chunk of Lancashire cheese — just £4. Tickets sold out faster than Oasis. If you didn’t have one, you were not begging, borrowing or stealing your way in. Even plaintive food journalists were left empty-handed.

So you’re doing these ’94 prices, Trevor,” I said to Gulliver around that time. “I can’t get in!

“I don’t give a f***,” came his characteristically blunt reply. “Honestly, I’ve had these boys pestering me for a table too.”

“Who, me?”

"Eh? No, Oasis. I ain’t gonna give it to ’em."

No, Oasis. I wasn’t giving it to them — Trevor Gulliver

The demand did not just reflect a yearning for an unusually cheap lunch, but also the deep affection in which St John is held. Its impact on British food can hardly be overstated. When Gulliver, Henderson and front-of-house master Jon Spiteri opened on St John Street in 1994, it was with a singular, almost bloody-minded vision that felt completely radical for its time.

There were reams of appreciation written around the 30th anniversary. They tended to celebrate the influence of its nose-to-tail ethos, its minimalist, white-walled, gallery-style interior, and its reappropriation of “British” as a style of cooking — pitched somewhere between a pub lunch and a Victorian banquet, equal parts humble and historic.

I loved absolutely everything about it: the attitude, the look, the food, the wine.

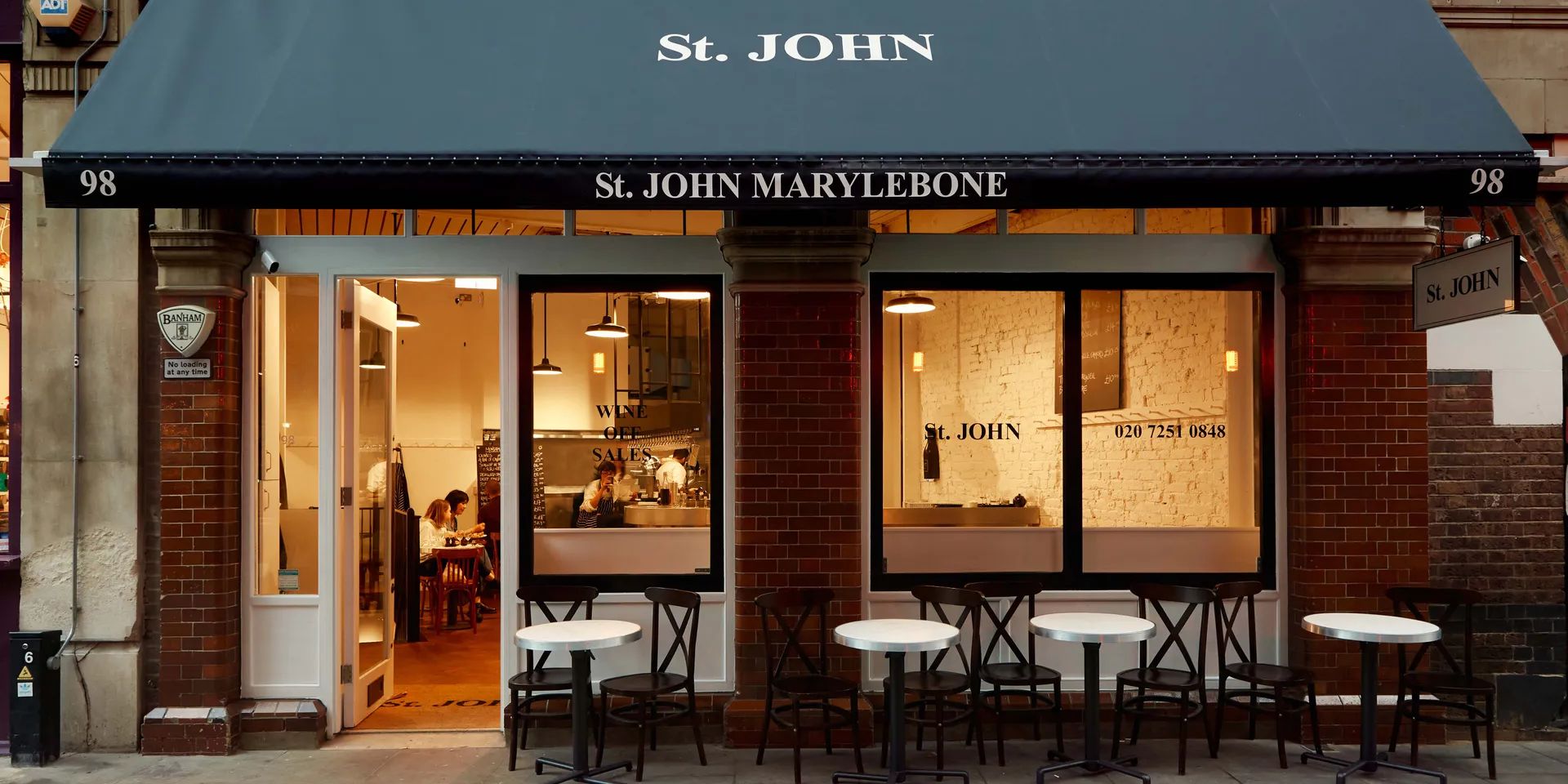

Naturally, much was made of Anthony Bourdain’s endless praise for what he once called “the restaurant of my dreams.” “I loved absolutely everything about it: the attitude, the look, the food, the wine,” he wrote of his first visit — after which he made a point of returning every time he was in London. His imprimatur helped turn St John into a culinary pilgrimage, a rite of passage for every food-minded traveller passing through the city. St John Bread & Wine followed, then another bakery, and finally a Marylebone branch. But the spiritual home remains St John Street, where that iron staircase still leads up to a room so familiar now you forget how strange it once seemed.

As with the band Gang of Four, it has often felt as though every chef who has worked at St John has gone on to start their own good restaurant. Lee Tiernan of Black Axe Mangal, James Lowe from Lyle’s, Tim Siadatan who founded Trullo and Padella, Ravneet Gill, Anna Hansen — all radically different chefs who began their careers under Fergus and Trevor’s tutelage. Spiteri’s sons, Lorcan and Fin, have their own successful spot, Caravel; the Henderson children are making their way through hospitality too. Thirty-one years on, British hospitality is infused — literally and metaphorically — with St John DNA.

If St John was to close tomorrow, it would still be the most important restaurant in London for thirty years more.

At the time of the anniversary, Nîcolas Payne-Baader, founder of Slop Magazine and front of house at St John Marylebone, remarked:

“If St John was to close tomorrow, it would still be the most important restaurant in London for thirty years more.”

When Gulliver brusquely dismissed Oasis’s request for a table, it was a joke — but also a proof of the point. Like the great rock stars, the great restaurateurs know you have to stick to your guns, and that winding people up from time to time is part of the show.

Come on in the Chablis lovely, Your new home of drinks.

Stay up to date with all the latest from House Of Decant.